Where did the “cyber” in “cyberspace” come from? Most people, when asked, will probably credit William Gibson, who famously introduced the term in his celebrated 1984 novel, Neuromancer.

It came to him while watching some kids play early video games. Searching for a name for the virtual space in which they seemed immersed, he wrote “cyberspace” in his notepad. “As I stared at it in red Sharpie on a yellow legal pad,” he later recalled, “my whole delight was that it meant absolutely nothing.”

How wrong can you be? Cyberspace turned out to be the space that somehow morphed into the networked world we now inhabit, and which might ultimately prove our undoing by making us totally dependent on a system that is both unfathomably complex and fundamentally insecure. But the cyber- prefix actually goes back a long way before Gibson – to the late 1940s and Norbert Wiener’s book, Cybernetics, Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, which was published in 1948.

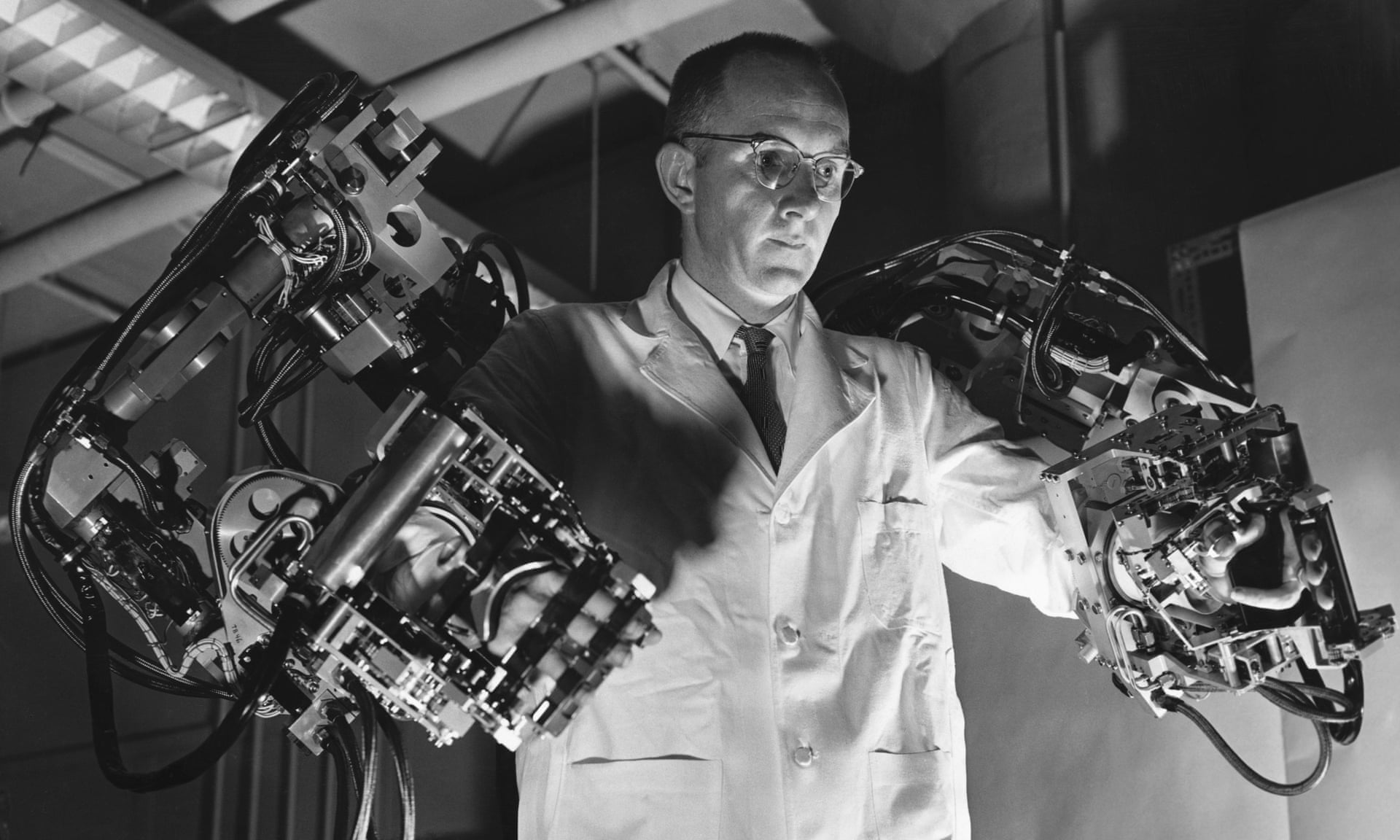

Cybernetics was the term Wiener, an MIT mathematician and polymath, coined for the scientific study of feedback control and communication in animals and machines. As a “transdiscipline” that cuts across traditional fields such as physics, chemistry and biology, cybernetics had a brief and largely unsuccessful existence: few of the world’s universities now have departments of cybernetics. But as Thomas Rid’s absorbing new book, The Rise of the Machines: The Lost History of Cybernetics shows, it has had a long afterglow as a source of mythic inspiration that endures to the present day.

This is because at the heart of the cybernetic idea is the proposition that the gap between animals (especially humans) and machines is much narrower than humanists believe. Its argument is that if you ignore the physical processes that go on in the animal and the machine and focus only on the information loops that regulate these processes in both, you begin to s

In order to explain how we’ve got so far out of our depth, Rid has effectively had to compose an alternative history of computing. And whereas most such histories begin with Alan Turing and Claude Shannon and John von Neumann, Rid starts with Wiener and wartime research into gunnery control. For him, the modern world of technology begins not with the early digital computers developed at Bletchley Park, Harvard, Princeton and the University of Pennsylvania but with the interactive artillery systems developed for the US armed forces by the Sperry gyroscope company in the early 1940s.

From this unexpected beginning, Rid weaves an interesting and original story. The seed crystal from which it grows is the idea that the Sperry gun-control system was essentially a way of augmenting the human gunner’s capabilities to cope with the task of hitting fast-moving targets. And it turns out that this dream of technology as a way of augmenting human capabilities is a persistent – but often overlooked – theme in the evolution of computing.

startling similarities. The feedback loops that enable our bodies to maintain an internal temperature of 37C, for example, are analogous to the way in which the cruise control in our cars operates.

Dr Rid is a reader in the war studies department of King’s College London, which means that he is primarily interested in conflict, and as the world has gone online he has naturally been drawn into the study of how conflict manifests itself in the virtual world. When states are involved in this, we tend to call it “cyberwarfare”, a term of which I suspect Rid disapproves – on the grounds that warfare is intrinsically “kinetic” (like Assad’s barrel bombs) – whereas what’s going on in cyberspace is much more sinister, elusive and intractable.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Your comments...